A follow-up to navigating accountability in Southeast Asia's rave subculture

A sexual and psychological abuse case involving Filipino artist Teya Logos has rocked the Manila and Southeast Asia scene.

Content warning: the following article deals with matters of sexual assault. Reader discretion is advised.

On Monday, April 21, a series of online statements posted on Instagram shed light on a history of sexual and psychological abuse perpetrated by Filipino DJ and producer Teya Logos.

A first statement from Logos herself established several instances in which the artist had abused her platform and status to take advantage of at least two unnamed victims. In her post, she acknowledged a “history of dangerous behavior,” citing a porn addiction and objectifying women, and stated that her recent break had been an act of accountability.

Her post was promptly followed by statements from two victims, Fie and Sofa, sharing detailed accounts of grooming and abuse in their encounter with Logos, dating back as far as age 13 for the latter. Their statements included a call for accountability addressed to their abuser and the community at large, including deplatforming Logos from public and community spaces where she holds power, taking financial responsibility towards her victims, and acknowledging the harm caused.

Fie’s post also criticized Logos’s framing of the incident as merely cheating on her partner, shifting the narrative away from survivors. This current framing remains the dominant narrative of her current Instagram statement, whereby her “break as an act of accountability” focuses first on “hav[ing] cheated on [her] partner twice,” only admitting to sexually harassing women later in the statement.

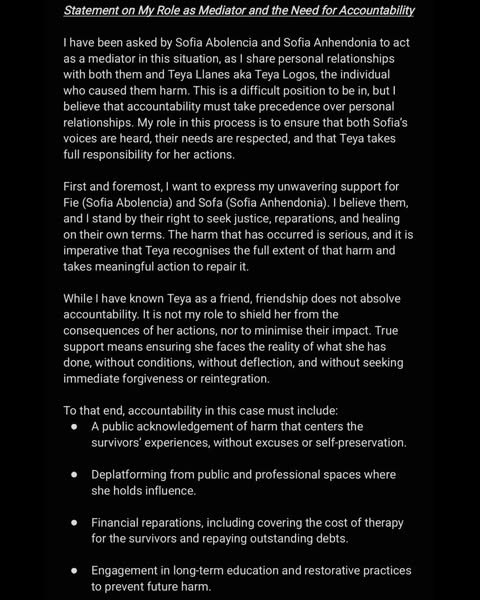

DJ and producer Jorge Wieneke, known as obese.dogma777, pillar of the Manila scene, also issued a statement on his role as mediator in this case, trying to seek justice for the victims and holding Logos accountable. Building upon the demands made by the victims, he also called for educational and restorative practices to prevent future harm, reminding the broader community to respond to harm through survivor-centric approaches.

The following day, Vietnamese performance artist Chaulichi posted an Instagram story revealing she had also experienced sexual abuse at the hands of Logos back in 2023.

Several organizers and collectives that previously worked with Logos have since come forward on social media to express support for the victims while monitoring the story for future developments, particularly efforts from Logos to demonstrate meaningful accountability.

Bussy Temple co-organizer Zenon, also known as Metamoksha, wrote in an Instagram story about the precariousness of the rave scene as a catalyst for potentially harmful behaviour, exacerbated by the presence of alcohol and substances: “none of us are exempt from abusive or harmful behavior.”

These words hold truth in grassroots-led spaces like rave subcultures, where there is little to no authority to regulate the behaviour of their members. The onus falls on the community to recognize and respond to harmful behaviour, and for perpetrators to acknowledge the harm they have caused, and how to meaningfully pursue accountability.

This also raises legitimate questions on how sexual harassment can fit within the framework of rehabilitative justice, which seeks not to punish but to focus on the root causes of crime through restorative and educational practices to allow criminals to re-enter society.

A constructive approach to this would incentivize individuals to understand the importance of accountability and reparations, both from a victim and perpetrator’s point of view, making them more capable of addressing harm in the event that they ever engage in harmful behaviour. Sheltering people from the possibility of perpetrating harm leaves them unable and/or unwilling to acknowledge their own shortcomings, only hindering restorative practices that require said acknowledgement in the first place.

Of course, the core component of rehabilitation entails a commitment to changed behaviour. In the case of Teya Logos, the statements of the many victims who spoke up so far show there has yet to be any intent to change. The opposite took place, whereas apologies to victims fell flat as a result of persistent harmful actions placing the broader community at risk.

With this new public attention given to the case, there is hope to see Logos take concrete actions towards reparations, including covering therapy costs of her victims, and seeking professional help for addictive tendencies that have fuelled her predatory behaviour.

Public acknowledgement of the case, albeit clumsy, and platforming the accounts of her victims provides an example of a first step towards accountability, one that strongly contrasts with how Indonesian band Gabber Modus Operandi (GMO) went about their own sexual abuse case a few years ago. Decent, earnest attempts at accountability should not be praised — it’s in the fact the bare minimum we should be expecting — but they are worth noticing when previous cases evolved amid such murky waters.

This case also comes at a time when trans rights are increasingly threatened by right-wing conservative forces across the globe, fuelled by the likes of notorious transphobic activist J.K. Rowling. These dangerous rhetorics seek to paint trans people, particularly trans women, as predators in disguise.

It goes without saying, transphobia has no place in rave subcultures, regardless of who the abuser is, and none of this should be used to invalidate Logos’s gender identity.

Nonetheless, cases like this will still likely make it that much more difficult for trans women to get acceptance, especially in a region such as Southeast Asia, where queer rights remain limited at best.

Perhaps another important takeaway from this scandal is the need to move beyond idolizing artists, performers, and organizers in the regional scene. The Southeast Asian rave scene isn’t as well established its North American, European, or Australian counterparts, with scarce collectives and spaces at times. As such, it becomes easy for us to put performers who quickly rise to the top on a pedestal, making them an unofficial face of the scene.

Sexual abuse, most studies agree on that, is in fact a power dynamic, one whereby the perpetrator feels empowered to take advantage of the victim, who can sometimes also be subdued or in a weakened state of mind. According to Sofa’s statement against Teya Logos, this power dynamic was unequivocally at play here: “During her rising popularity, Teya […] deliberately taunt{ed] me with her success, leveraging her achievements to exacerbate my sense of inadequacy.”

Worshipping false idols is a cardinal sin in the Bible after all; far be it from me to turn this entry into a religious studies essay, but there might be a lesson in there.

By putting less emphasis on performers, focusing instead on the music, we give them less room to abuse their status in such manner. We also make ourselves more open to holding them accountable if they slip up, rather than seeking to defend and justify harmful behaviour in a fruitless “stan war”.